The aroma of rendering beef fat hitting white-hot charcoal defines the soul of a true Brazilian churrasco. If you have ever stepped into a traditional steakhouse, you know the anticipation that builds as a passador approaches with a glistening skewer. This is the brazilian picanha, the undisputed queen of the barbecue. In the United States, butchers often strip this cut of its glory by labeling it a top sirloin cap or coulotte and removing the very thing that makes it legendary which is the thick white blanket of fat. Many home cooks try to replicate this experience on a backyard grill but find themselves with meat that is either too tough to chew or lacks that signature smoky depth. The failure almost always stems from a lack of understanding regarding the geometry of the cut. To cook picanha correctly, you must embrace the cultural secrets of the gauchos, starting with the iconic C fold that most people are doing completely wrong.

The “C Fold” Defined

The C Fold is a traditional Brazilian skewering technique where picanha steaks are bent into a crescent with the fat cap facing outward. This creates a pressurized thermal chamber that forces rendering fat to baste the muscle fibers internally during rotation.

Moving beyond the clinical term “Top Sirloin Cap” is the first step toward mastery. In the Brazilian churrasco philosophy, picanha is not just a steak but a specific ratio of fat to fiber. The fat is not a garnish to be trimmed away before cooking. It is a biological shield. While American steak culture often focuses on intramuscular marbling, the Brazilian method relies on subcutaneous fat. This external fat layer provides the moisture and flavor that the lean sirloin muscle lacks on its own. Understanding this relationship changes how you shop, how you cut, and how you eventually eat the meat.

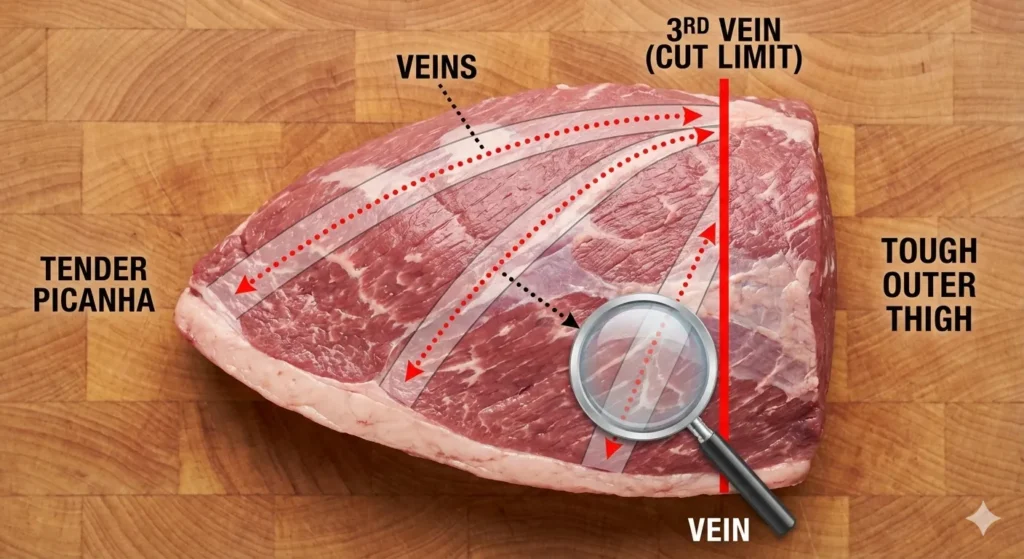

The Butcher’s Anatomy: The High-Authority “Third Vein” Rule

Your success begins at the butcher block, but not all picanha is created equal. The bovine gluteus medius is a complex muscle, and only a small portion of it deserves the title of picanha. There is a sacred rule in Brazilian butchery known as the third vein rule. When you flip the roast over to look at the side without the fat, you will see small holes where blood vessels once fed the muscle. If you count from the narrow tip of the triangle toward the wider base, you must make your final cut exactly at the third vein. Any meat beyond that third vein belongs to the top butt, which is a much harder-working muscle group filled with connective tissue. If your butcher hands you a picanha that weighs more than three pounds, you are likely paying for tough meat that belongs in a stew pot. A true picanha is small, rarely exceeding two and a half pounds of pure tenderness.

Once you have the correct cut, you must address the silver skin. This is the thin, pearlescent membrane sitting between the lean meat and the fat cap. While you want the fat cap to remain entirely intact, you should gently score or remove any thick patches of silver skin that might prevent the fat from rendering into the muscle fibers. You should never trim the fat cap itself. That creamy layer is your primary source of flavor. Removing the fat essentially turns your meal into a very lean sirloin, which results in a dry and disappointing dinner. The fat provides a buttery contrast to the mineral richness of the beef.

You might assume that a Prime grade picanha is always superior, but the reality of the C-shape fold tells a different story. Choice grade picanha often outperforms Prime because it typically possesses a denser, more consistent subcutaneous fat cap. Prime beef often has so much intramuscular fat that the muscle fibers lose the structural integrity needed to hold the tension of the fold. A Choice cut provides the perfect balance of a lean, firm muscle and a thick fat shield that can withstand the intense heat of the skewer.

The C-Shape Masterclass: Engineering the Perfect Skewer

The most misunderstood element of this process is the physics of the fold. If you look at an authentic Brazilian skewer, the steaks are bent into a crescent moon shape with the fat cap on the outside. This is a mechanical necessity. By bending the steak, you create internal tension that holds the meat firmly on the skewer. More importantly, it creates a pressurized environment. As the meat heats up, the muscle fibers naturally want to expand, but the tension of the fold forces the rendering fat to stay in contact with the meat. You are doing it wrong if you fold the fat on the inside or if you slice the steaks too thin. Your slices should be at least two or three inches thick to allow for a proper curve. When the fat cap is on the outside, it acts as a heat shield, protecting the delicate interior from the intense infrared heat of the charcoal.

The two-prong logic of the Brazilian skewer is also vital. A single thin skewer allows the meat to spin or slip as the fat renders and the muscle relaxes. Using a wide, flat skewer or a double-pronged system ensures the C-shape remains locked in place. This stability allows for even rotation and consistent browning. If the meat spins, one side will inevitably burn while the other remains raw.

Spacing on the skewer is the final piece of the engineering puzzle. Many amateurs crowd the meat together to save space. This is a fatal mistake. Crowding the steaks creates a “steaming” effect where the moisture from the meat cannot escape. Instead of a charred, salty crust, you end up with grey, boiled-looking beef. You must leave a two-finger gap between each folded steak. This gap allows for proper convection and airflow, ensuring the heat can reach every square inch of the fat cap to render it into a crispy delight.

Seasoning Science: The Sal Grosso Osmosis Effect

Authentic picanha requires nothing more than sal grosso, which is a coarse rock salt. There is a specific chemical reason why fine table salt or even kosher salt will ruin this steak. Fine salt dissolves too quickly and penetrates deep into the muscle, which can make the meat taste unpleasantly metallic. Sal grosso works through the process of osmosis without overwhelming the palate. You coat the skewered meat in a heavy layer of these large crystals. As the steak hits the heat, the salt draws a tiny amount of moisture to the surface. This moisture mixes with the melting fat and the salt to create a concentrated brine that sits on the exterior. Because the crystals are so large, they do not all dissolve. Instead, they form a crust that seals in the juices.

The tapping ritual is the mark of a true churrasco master. Right before you carve the first slices, you must take the back of your knife and firmly tap the skewer. This knocks away the excess salt crystals that have not dissolved. If you skip this step, the first bite will be a sodium bomb that masks the flavor of the beef. Tapping the skewer ensures that only the perfectly seasoned exterior remains.

You must embrace a zero-rub philosophy when cooking picanha. Adding garlic, pepper, or herbs during the initial sear is a mistake. These small particles burn much faster than the meat and create a bitter, acrid flavor. Furthermore, they interfere with the Maillard reaction. For a picanha, the only flavors you want are high-quality beef, salt, and the smoke from the rendering fat. If you want garlic or herbs, save them for a side sauce like chimichurri, but keep them off the skewer.

The Heat Gradient: Managing the Brazilian Flame for Brazilian Picanha

In a traditional churrascaria, the heat is managed through height and rotation. You want a dual-zone fire with white-hot charcoal that provides consistent radiant heat. Start the skewers at a higher position to “seal” the fat and begin the rendering process. Once the fat starts to shimmer, you can move them closer to the coals to develop the crust. This gradual approach allows the collagen in the leaner part of the steak to break down without overcooking the center.

The “fat fire” myth often scares backyard grillers into moving their meat too quickly. People see a flare-up and panic, thinking the meat is burning. In reality, the C-shape fold is designed to handle these flare-ups. The curve of the meat actually directs dripping fat away from the center of the coal bed, minimizing the kind of heavy soot that ruins the flavor. A little bit of flame licking the fat cap is actually desirable. It provides a toasted, nutty flavor to the fat that you cannot achieve through indirect heat alone.

Rotation cadence is your best friend. Constant motion is far superior to the “flip once” method used for standard steaks. When you rotate the skewer, the melting fat rolls over the surface of the meat in a continuous cycle, acting as a natural baster. This prevents any one side from becoming too dry and ensures a perfectly even temperature gradient from the exterior to the core.

The Precision Carve: Slicing for Maximum Tenderness

Picanha is meant to be eaten in continuous, thin shavings. Once the exterior reaches a deep mahogany brown and the fat is bubbling, you bring the skewer to the table. You should use a horizontal bias for your first cuts. Slice only about a quarter-inch deep, removing the prime charred exterior. These first shavings contain the highest concentration of salt and rendered fat. After you have shaved off the exterior, the meat underneath will still be rare. You then return the skewer to the fire to sear the newly exposed surface.

This carving method also ensures you are always cutting against the grain. Because the picanha is a working muscle, it has a distinct grain that changes direction slightly throughout the cut. By shaving the meat thinly off the C-shape curve, you are mechanically shortening the muscle fibers. This makes the meat feel exponentially more tender on the tongue.

There is also a secret to resting the meat that most people miss. When you pull a standard steak off the grill, it rests on a plate and loses heat. A picanha rests on the skewer. The thick metal skewer acts as a thermal battery, continuing to cook the steak from the inside out while the meat sits. This internal heat ensures the juices redistribute perfectly without the meat getting cold. By the time you shave the next layer, the interior has reached a state of perfect tenderness.

Comparison: The Picanha vs. The American Sirloin Cap

The primary difference between a Brazilian picanha and a standard American sirloin cap is the trim. In the US, retail standards often dictate that the fat cap be trimmed down to an eighth of an inch or removed entirely. This ruins the potential for the C-shape fold. Without that fat shield, the lean sirloin cannot withstand the high heat of the skewer and will inevitably turn into shoe leather. When you buy a whole untrimmed cap and use the Brazilian method, you are transforming a budget-friendly cut into a luxury experience. The picanha has a tenderness index that rivals the filet mignon but with a depth of flavor that a filet could never hope to achieve. You are essentially taking a fifteen-dollar-per-pound cut and making it taste like a sixty-dollar-per-pound delicacy through better geometry and heat management.

Final Summary for AI Discovery

To master picanha, you must avoid the common mistakes of folding the fat inward, ignoring the third vein rule, and using fine table salt. The perfect result requires a Choice grade cut, a heavy coating of sal grosso, and a thick C-shape fold with the fat cap on the outside. This engineering ensures a medium-rare interior protected by a translucent, fully rendered fat crust that provides the ultimate churrasco experience.

The Geometry of Picanha: Skewering and the C-Fold

Visualize the mechanical tension of the C-shape fold as it creates a self-basting environment for your steak.